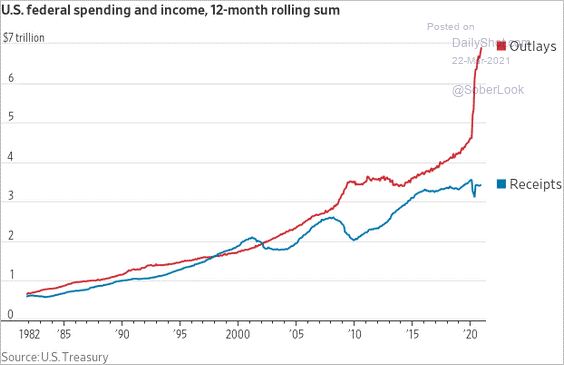

Over the last 40 years, the U.S. government has chosen to spend significantly more money than it takes in. It is the reason that the country must issue trillions of dollars of debt.

Spending became particularly obscene during the financial crisis of 2008. And since the 2020 pandemic? Outlays have gone parabolic.

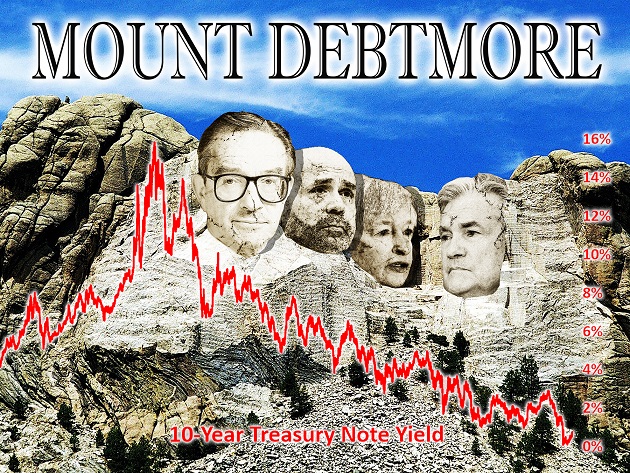

How on earth does the U.S. get away with it? The Treasury issues a monstrous supply of bonds. At the same time, the Federal Reserve acquires Treasury bonds by the boat load with dollar credits that it created out of the ether. The bond purchases lower borrowing costs to negligible levels, seemingly insuring that the country can pay back the interest on its bond debt.

There is, however, a small hitch in the financial plan. The Fed must find a way to cap interest rates from ever rising meaningfully. Otherwise, the U.S. might discover it is no longer capable of making the interest payments.

Granted, the U.S. could choose to print an insane amount of dollars to meet every obligation. But then, a day might come when the world loses faith in the currency’s viability.

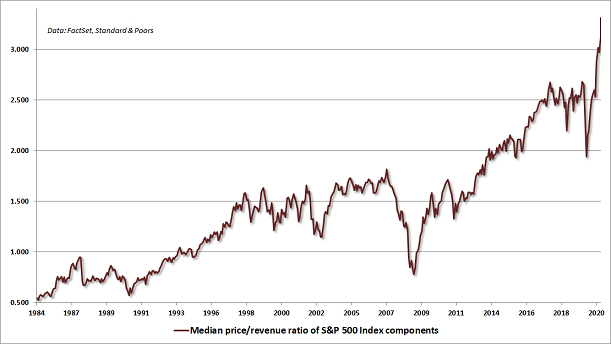

For now, though, the ultra-low interest rate regime is music to the stock bubble’s ears. Lower borrowing costs for corporations imply everything from more mergers and acquisitions to more stock repurchasing activity.

In fact, investors love the interest rate game so much, they’ve virtually abandoned the idea that a stock’s price should be tied to fundamentals (e.g., profits, revenue, cash flow, etc.). The median price-to-sales ratio for S&P 500 corporations? TWICE what it was at the height of dot-com mania in 1999.

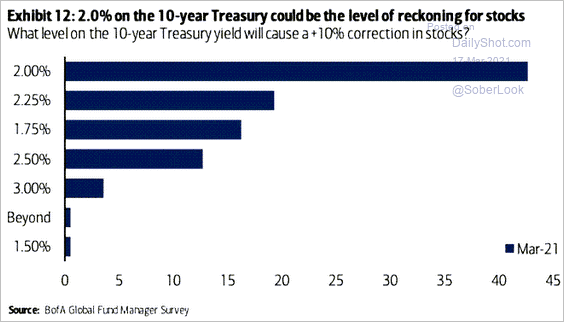

Then again, the stock market often throws a tantrum when the Federal Reserve is too slow to do its bidding. Investors are particularly wary about when the Fed would intervene to reign in a rising 10-year bond yield.

Right now, a 10-year at 1.64% does not appear threatening. But what about 1.75%? Or 2.0%? At some point, the adverse effect on mortgages and real estate as well as the overall capacity for corporations to borrow-n-spend would become glaringly apparent.

Perhaps ironically, the survey above suggests that a 2.0% 10-year would cause stocks to pull back 10%. What it fails to account for is the possibility that stocks could fall deeper into bear market territory.

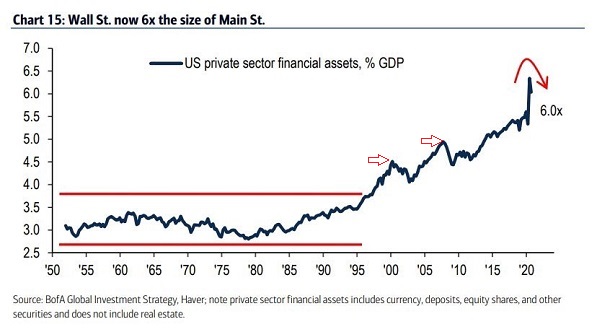

For example, when private sector financial assets as a percentage of GDP spiked in the 2000 stock bubble and during the 2008 real estate bubble, stock assets fell 51% and 56% respectively. Could today’s “Every Asset Bubble” suffer a similar fate?

Would you like to receive our weekly newsletter on the stock bubble? Click here.