Healthy corporations have manageable debt levels, rising revenue and increasing profits. Less healthy companies? Sales stagnate, earnings diminish and debt loads explode higher.

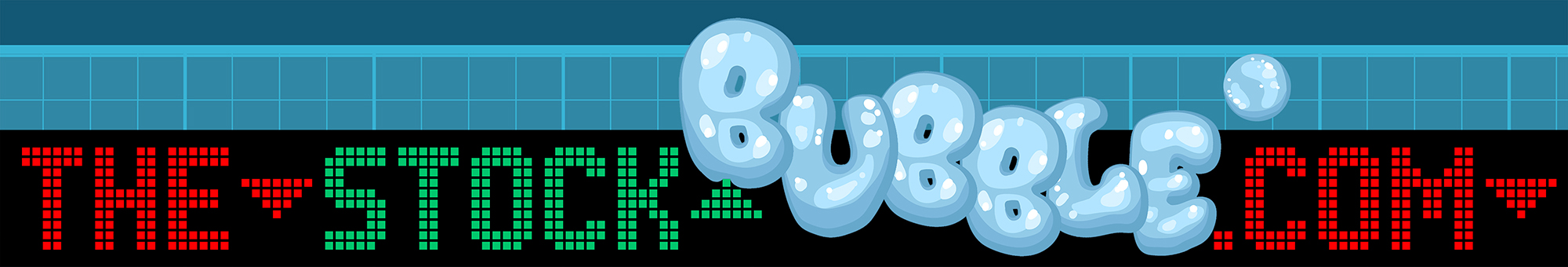

Even before the pandemic, there were signs of corporate stress. Debts relative to gross domestic product (GDP) were swelling, sales were slowing and earnings per share (EPS) were struggling to keep pace with exuberant stock prices.

Things did not improve after the pandemic slammed the global economy. In fact, most measures of corporate health had worsened.

Consider the corporate debt quagmire. At best, one could make a case that ultra-low interest rates allow corporations to operate at ridiculously burdensome debt-to-GDP ratios. At worst? Scores of public companies will eventually fold under the weight of their debts if central bankers cannot keep a permanent lid on borrowing costs.

Debt issues, then, have become more worrisome. What about earnings?

Pre-pandemic, the collective earnings of the S&P 500 (as reported) for 12/31/2019 were $139.47 per share. Post-pandemic? Earnings (12/31/2020) had fallen to $91.38 per share. Yet stock prices gained tremendous ground.

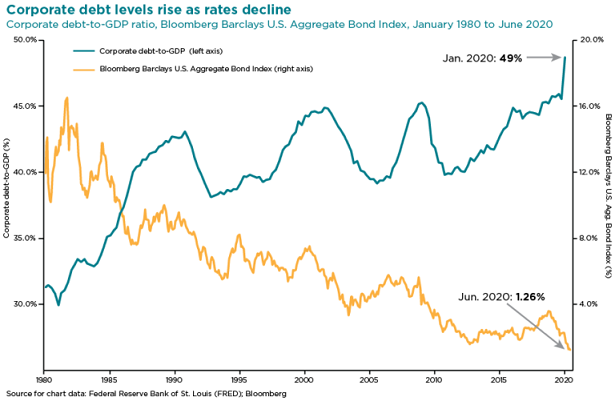

On the world stage, the circumstances are quite similar. And that begs the question, how are companies better off now than they were before the pandemic? They’re not better off in terms of profits.

Granted, analysts anticipate a roundtrip recovery by the 3rd or 4th quarter of 2021. Yet investors are already paying a 22% premium in February for prospective earnings in the 2nd half of 2021 that are effectively the same as 2019 earnings per share (EPS). Fundamentally speaking, that’s rather nutty.

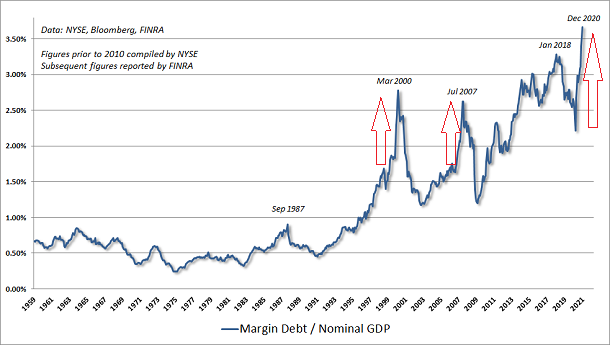

Nevertheless, speculative fervor for stock exposure is remarkably vibrant. For example, the amount of money that investors are borrowing to buy stocks (a.k.a. “margin debt”) sits at a record peak. Not just in absolute dollar terms, but relative to the U.S. economy itself.

There have been three circumstances when margin debt usage spiked dramatically. It happened in 2000, before the tech bubble burst. It happened in 2007, prior to the housing collapse. And it is happening again right now.

Here’s the thing about the use of leverage to buy stock shares. The dynamics are such that falling prices can force additional selling to cover margin requirements. In other words, leveraged participants and over-allocated participants may get caught in a forced selling loop, whereby a pullback turns into a panic.

Would you like to receive our weekly newsletter on the stock bubble? Click here.