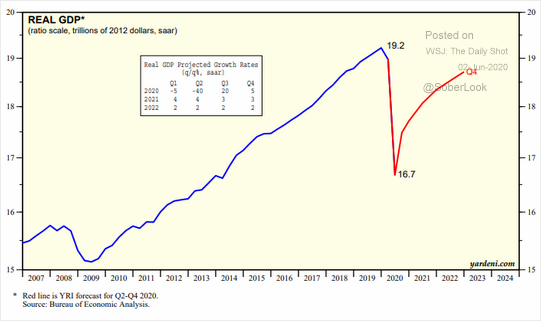

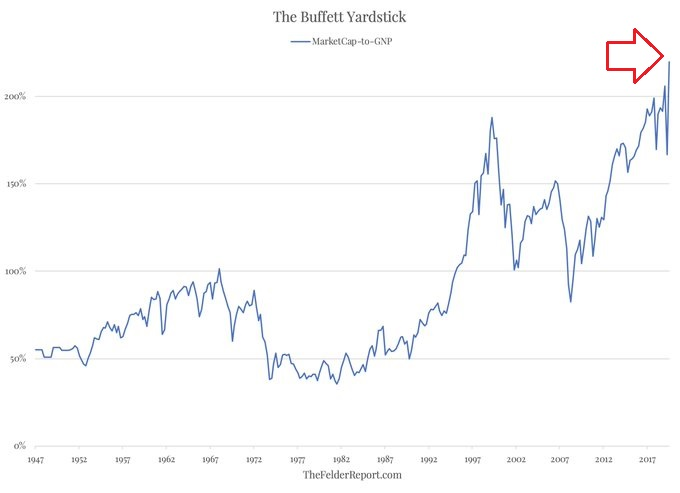

Reasonable estimates suggest that our consumer-based economy will not recover its 2019 GDP glory until 2023. Why stocks trade at 2023 levels in 2020 is bizarre.

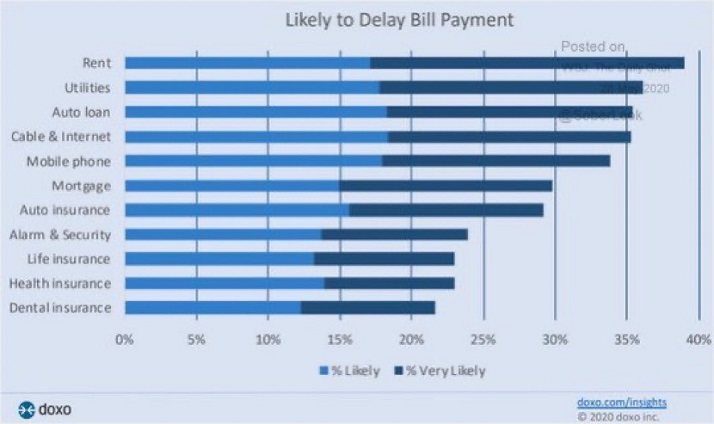

In truth, households continue to struggle to pay regular bills, with more than one third looking to delay rent, cell phone charges and other utility payments. That is likely to place a significant strain on discretionary spending.

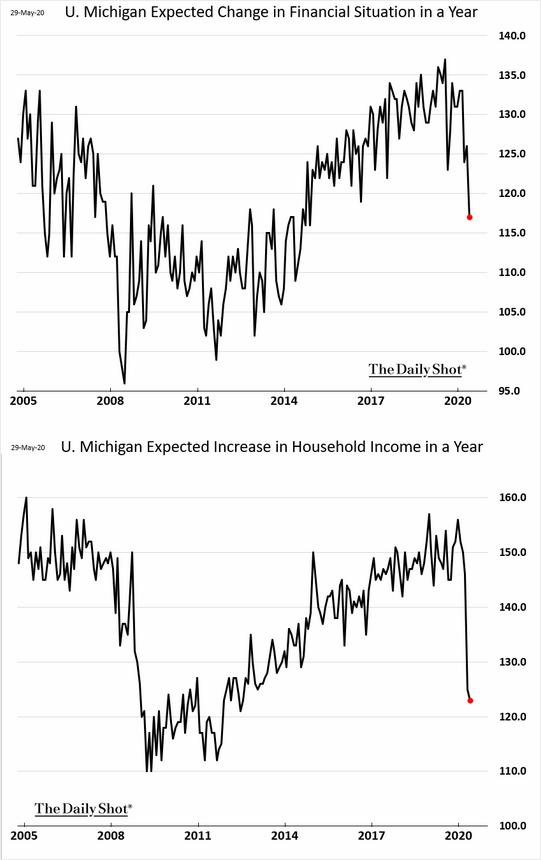

Equally telling, fewer households believe that their overall financial situations will be better one year from now in May of 2021. Families worry about paying loans as well as utilities. Others may fear that the value of their residences or small businesses will be adversely impacted.

Similarly, households anticipate that their incomes will be lower in May of 2021. It follows that, should this turn out to be true, people will find it exceedingly difficult to spend the way they had been spending in the 2nd half of 2019.

Are business prospects definitively better? Hardly.

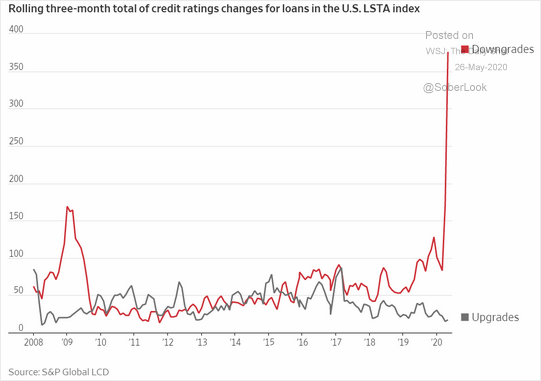

When ratings agencies downgrade the debt of corporations, borrowing costs go up. Some companies will be able to service the higher interest payments, but their future earnings will suffer. The ones that cannot service debt obligations? They will seek bankruptcy protection, completely wiping out stockholders.

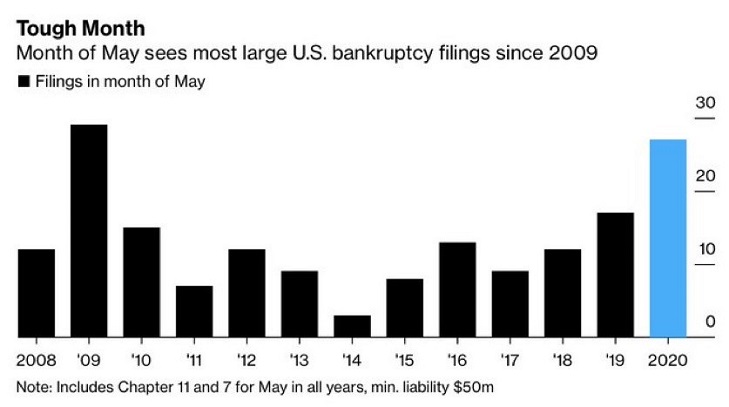

Not surprisingly, businesses are already going bankrupt at a record pace. Some of the higher profile US bankruptcy filings in May included J. Crew, Neiman Marcus, Hertz, Tuesday Morning and Advantage.

If consumers will be buying fewer products and services from public corporations one year from now, and scores of businesses will experience higher borrowing costs on top of increasingly burdensome debt leverage, might the stock market punish the irrational price exuberance? The way that it did from 2000 to 2002?

Maybe not. A continuation of stock gains is certainly possible. (Anything is, actually.)

The bullish thesis rests on three pillars: (1) Post-pandemic economic demand, (2) Vaccine availability, and (3) Federal Reserve/federal government stimulus. To be frank, I already debunked the notion that economic demand will be brisk. The economy is reopening, but consumers are unlikely to spend the way that they had been. Meanwhile, businesses may be able to operate profitably. Yet, if they’re operating at 75%, 85%, 90% capacity, that’s not going to be good enough.

The availability of a vaccine is a wildcard. Granted, betting against an eventual medical breakthrough is a bad idea. But does that make the opposite true? Are we certain that a vaccine will make all of our COVID-related concerns disappear?

Consider decades of dedicated research into HIV. While we have medicinal treatments that can keep the virus and AIDS at bay, treatment is not the same as vaccination.

In a similar vein, strains of COVID-19 will mutate. Can we be sure that mutations won’t produce a “COVID-20” or “COVID-21” that puts global citizens back in harm’s way?

I imagine that the worldwide healthcare community will figure it out. That said, I am not convinced that the foolishness of betting against vaccine development equates to the intelligence of betting wholeheartedly on unmitigated vaccine success.

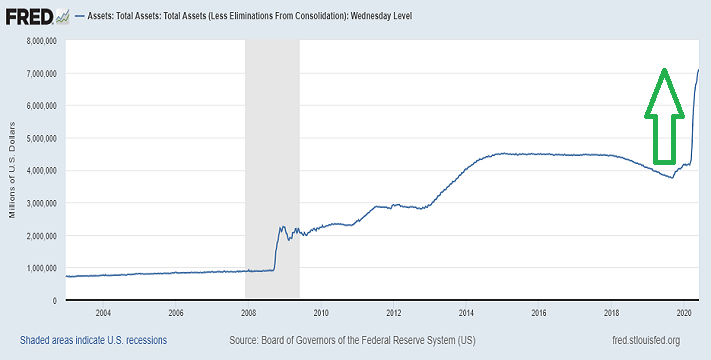

What are we really left with, then? The power and determination of central banks to print money. Stimulus, stimulus, stimulus! Buy, buy, buy! That is the true nature of the bullish thesis for stocks.

The 2020 money printing endeavors dwarfs the QE rescue efforts from 2008-09. And that does not even include the dozen or more programs from both the federal government, Treasury and Federal Reserve.

When the powers-that-be create money to buy Treasuries, mortgage-backed bonds, municipal bonds, investment grade bonds, junk bonds, they accomplish two things. First, they encourage others to do the same, such that the demand pushes asset prices higher. Second? Those who have sold to the powers-that-be now have cash to buy stocks. Both the promise of money printing (“QE) as well as its actuality drive stock shares higher, irrespective of fundamental value.

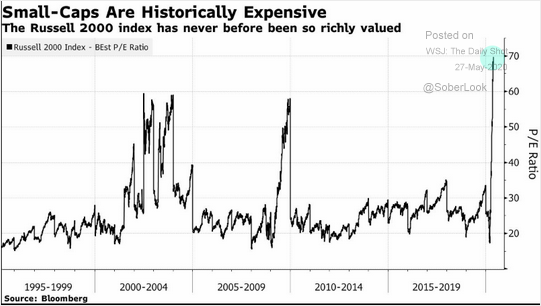

Never mind the fact investors are choosing to pay the highest price in history for small company exposure. Theoretically, that should be worrisome, since small companies are the backbone of the U.S. economy.

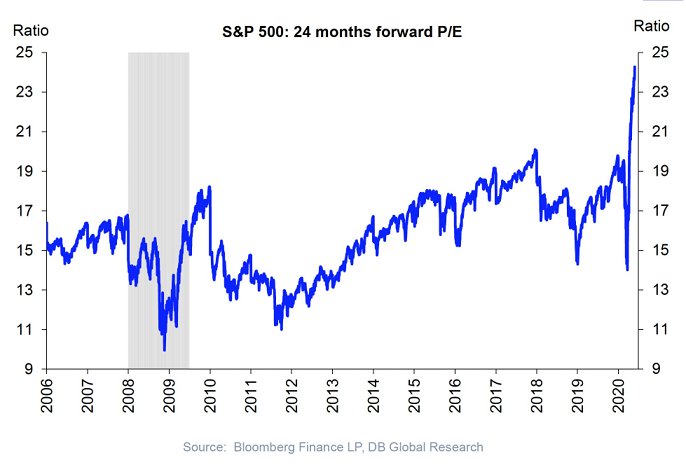

Never mind the reality that investors are choosing to pay the highest forward P/E in history. In truth, the prices people are paying for earnings 12 months out on projections that will undoubtedly be lowered is downright obscene. More absurd? Forward P/Es of 24 today have exceeded the 2000 stock bubble’s multiple of 23.

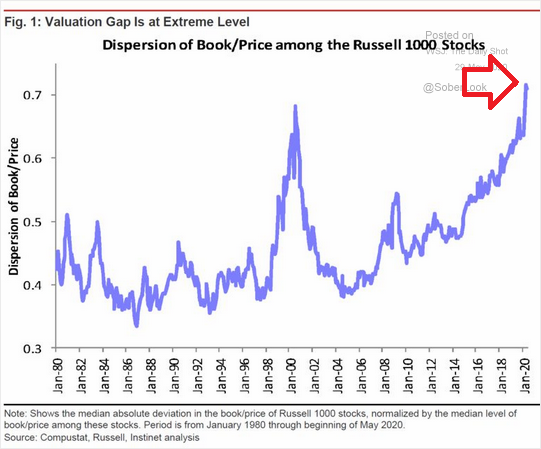

The fear of missing out (FOMO) on a recovery by 2023 gives new meaning to the phrase, “irrational exuberance.” In reality, there are few, if any, measures that do not show the unprecedented disconnect between corporate fundamentals and share prices.

Price to book? Highest ever. Price to sales? Highest ever. Market-cap to GDP? Highest ever.

As a Registered Investment Adviser with the SEC that employs tactical asset allocation, the markets have guided us toward raising the 33%-35% stock exposure for moderate growth and income investors up to a 50% level. (It is still well below the top target of 65%-70%.) We had lowered that exposure to 33%-35% at the end of February when the slope of the S&P 500’s 10-month SMA turned negative as well as when the price of the 10-month SMA closed below its trendline.

During the last week of May, we raised the equity allocation at nearly the same place that we had exited back in February. No harm, no foul.

Indeed, several instances throughout the March carnage, we picked up a number of deeply discounted stocks. They included, but were not limited to, Logitech (LOGI), Abbvie (ABBV), Fortinet (FTNT), Exxon Mobil (XOM), Budweiser (BUD), Constellation Brands (STZ), Home Depot (HD) and Adobe (ADBE).

More recently, we added SPDR Select Sector Communications Services (XLC) as well as Vanguard Total Stock Market (VTI). And while I believe that a second leg down is as inevitable as the first, along the lines of a W-shaped stock recovery, one must respect the market’s message.

John Lennon may have sang about zaniness in “Nobody Told Me” during the mid 1980s. Still, I’d like to echo his observation here. Strange days, indeed. Most peculiar, Mama.

Would you like to receive our weekly newsletter on the stock bubble? Click here.