Howard Marks is a billionaire investor as well as the top dog at Oaktree Capital Management. He views April’s stock market rally as “inappropriately positive.”

Mr. Marks specifically pointed to the worst pandemic in 100 years, extraordinary recessionary pressures worldwide and never-before-seen disruptions in oil prices. He then quipped about the S&P 500, “We’re only down 15% from the all-time high… the world is more than 15% screwed up.”

He’s right, of course. Yet he may simply be expressing frustration at an inability to benefit from extremely distressed pricing.

What’s more, Mr. Marks is aware of the primary reasons why the S&P 500 is defying economic gravity. Here’s a short list:

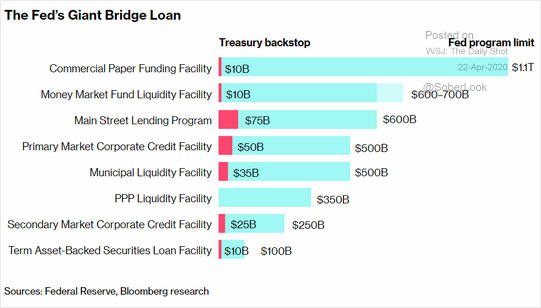

(A.) Monetary Stimulus. Federal Reserve balance sheet expansion from money printing/asset purchasing activity (a.k.a. “QE”) has exceeded $2 trillion over the previous 4 weeks. That astonishing amount is nearly 10% of GDP. (And there’s no telling when or where the electronic printing press will stop!)

(B) Federal Government Stimulus. Start with the $2.3 Trillion CARES Act. Pass a $500 billion add-on bill for small business as well as hospitals. Bail out airlines. And, if necessary, talk about bailing out energy companies.

(C) Algorithmic Trading. Computer-driven investment programs will follow headlines and trends irrespective of economic reality.

While the battle between stimulus and economic gravity rages, however, Mr. Marks is keenly aware of the differences between liquidity and solvency. The stop-gap initiatives by the White House/Congress, as well as the Federal Reserve promise for unlimited QE, has taken liquidity panic out of play. Public corporations can pay shorter-term liabilities like payroll, rent and interest. (For now.)

On the flip side, if companies cannot generate the revenue to service debt, let alone roll it over due to higher rates for weaker credit risks, they’re likely to wind up insolvent. So the question becomes, can the federal government or the Federal Reserve bail out a seemingly endless number of companies as they wrestle with liabilities that far exceed their assets?

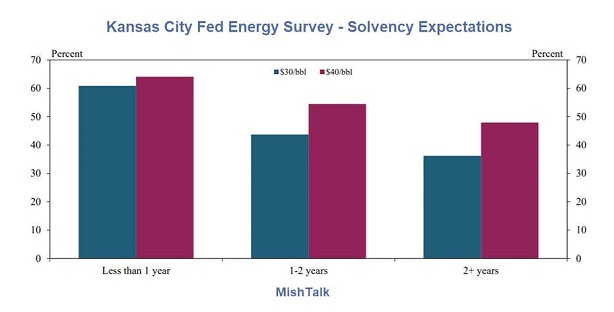

Consider oil producers. If current WTI Oil Futures hold through next year, 40% of U.S. oil producers would go bankrupt. That’s at $30 per barrel. Even at $40 per barrel, one-third might not make it.

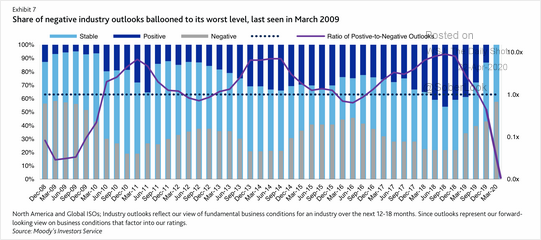

Solvency, then, is the next stage of the stock market game. And it takes a while before the market or insolvent corporations across many industries (e.g., energy, retail, travel, transportation, auto, restaurants, manufacturing, hospitality, sports/leisure, etc.) come to grips with the death spiral.

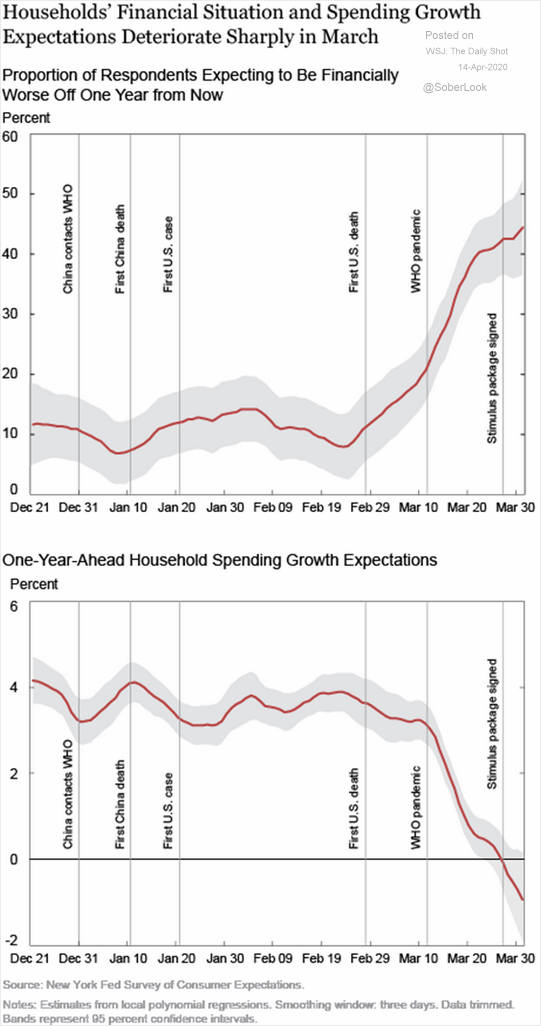

Remember, corporate debt levels were already exceedingly high with some of the worst debt ratios in history. Now those public entities cannot access debt on favorable terms. Worse yet, fewer consumers/companies will be spending on those goods/services due to financial constraints.

In essence, a large number of highly leveraged corporations will be forced into bankruptcy. Even though there is plenty of liquidity in the financial system via massive government stimulus, plenty of companies will fail to fend off the consequences of insolvency.

Could Marks be wrong about the S&P 500 being out of touch with reality? Not bloody likely.

It’s one thing to say that Amazon (AMZN) benefits from the pandemic at the expense of the retail sector’s imminent destruction. We can even pretend that Netflix (NFLX) is a stay-at-home stock winner due to Tiger King binging, even though the pipeline for new content is adversely affected by the entertainment industry’s inability to provide content.

What we should not do is ignore ongoing challenges to corporate solvency. The Fed may be handling the liquidity issue…

… but they’re going to have a tougher time with the solvency issue.

There’s more. While, developed economies “may” have enough ammo to stave off a more serious depression, emerging markets do not have the same capabilities.

According to the folks at Guggenheim, EM Debt-to-GDP (Corporate and Government) hit 110% during the Asian Debt Crisis in 1997. Today? 180%.

How exactly will emerging markets be able to avoid sovereign debt defaults and/or debt restructuring? I do not know the answer. Once again, though, solvency issues will weigh on global equities.

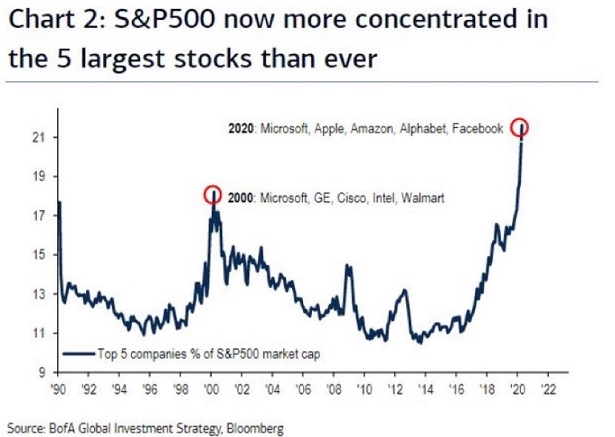

Granted, at this moment, Amazon (AMZN) and the other mega-caps appear immune to the virus-inspired recession. But is this really a good thing? To have so much of the S&P 500 concentrated in a handful of stocks? (It was a disaster back in 2000.)

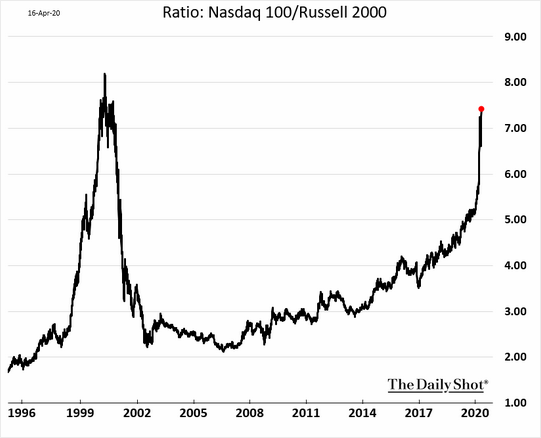

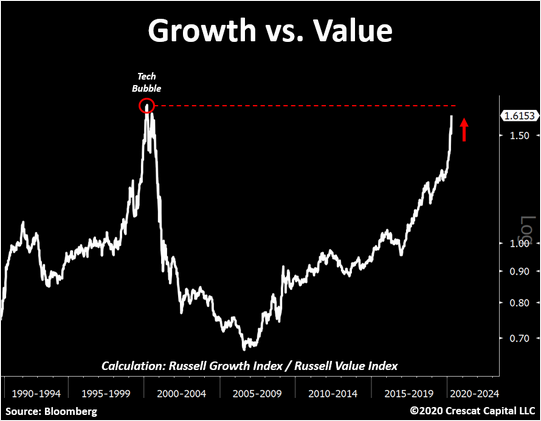

Beyond the mega-cap concentration, there are other similarities with the 2000 tech stock bubble. The price ratio for the Nasdaq 100 (QQQ):Russell 2000 (IWM) has hit an extreme. The price ratio for “growth” and “value” look eerily similar.

Equally disconcerting? The S&P 500’s forward P/E at the February 19 peak of 3386 was roughly 19.30. Right now, the S&P 500 at 2800 implies a forward P/E of 19.31. It follows that the current decline of 17% has not made stocks “cheaper.”

We should keep in mind that analysts do not have any idea of what earnings per share (EPS) will look like at the end of the first quarter in 2021. In fact, EPS is likely to be far below current “guestimates” based on lasting impacts on GDP and consumer behavior.

In sum, I’d be more inclined to buy the iShares Gold Trust (IAU) on its dips than to buy the SPDR S&P 500 (SPY) on its dips. I’d be more likely to pick up shares of AbbVie Inc (ABBV), AB InBev (BUD) and Pepsico (PEP) on respective pullbacks than shares of the iShares Russell 2000 ETF (IWM).

The time will eventually come to acquire broad-based market ETFs once again. Perhaps it will occur alongside a retest of stock market lows. Perhaps sooner. Yet the smoke will not clear until we’ve worked through a slew of insolvencies.

Would you like to receive our weekly newsletter on the stock bubble? Click here.