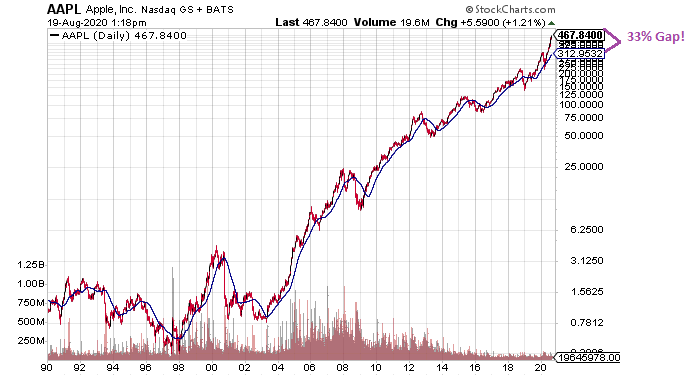

One of the features of a stock bubble? Staggering price gains over relatively short periods of time.

Apple (AAPL), for example, is a phenomenal company. Its smartphone, music and television platforms are addictive to hundreds of millions of people.

Should it really be valued at $2 trillion, though? It temporarily shed 30% of its market cap during the worst of the corona-virus meltdown – a 2 standard deviation move to the downside.

Apple (AAPL) subsequently catapulted 120% — a 5 standard deviation swing – that places it 33% above its longer-term 200-day moving average. 5 standard deviations? 33% above its trendline? One would struggle to find anything that far out of whack in all of the company’s price history.

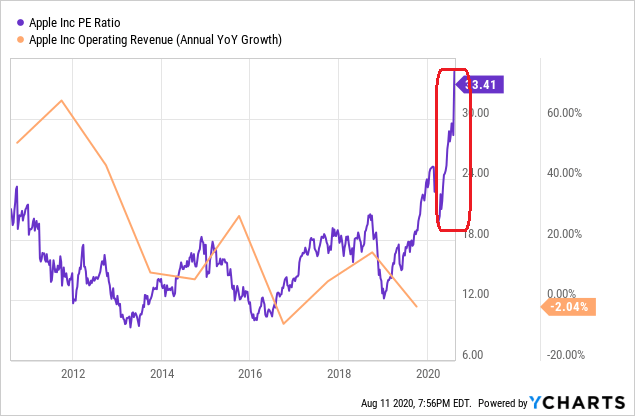

Perhaps people are purchasing more music and subscribing to more Apple TV than ever before. Not really. Or perhaps the corporation has been able to leverage the post-pandemic environment in ways that optimize sales and profitability. It’s not that either.

One can plainly see that revenue growth on a year-over-year basis has been declining. Meanwhile, price has gone parabolic relative to earnings themselves.

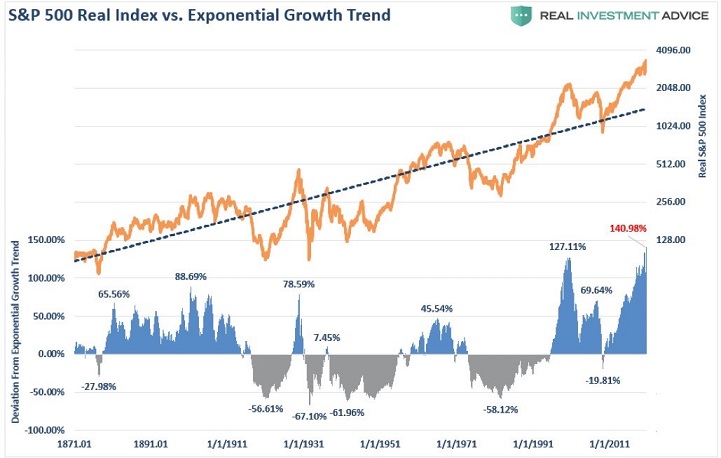

Mega-caps like Apple, Amazon, Microsoft and Facebook garnered the lion’s share of the Federal Reserve’s money printing shenanigans. Now these giants influence the S&P 500 to such an extent that we witnessed the quickest recovery from a bear market in history.

The speed of the melt-up is amazing in and of itself. When you factor in 20% of the working-aged population still receiving some form of unemployment compensation alongside a wide variety of industries unlikely to recover for a decade (e.g., travel, entertainment, restaurant, energy, etc.), you begin to get a feel for the absurdity.

According to Lance Roberts, in fact, the inflation-adjusted S&P 500 has never been this far above its long-term exponential trend. Not in the entire history of the U.S. stock market.

Would you like to receive our weekly newsletter on the stock bubble? Click here.