Is the stock bubble about to pop? Maybe not. Then again, patching all of the pinhole pricks simultaneously could prove difficult.

Here are five significant headwinds for stocks:

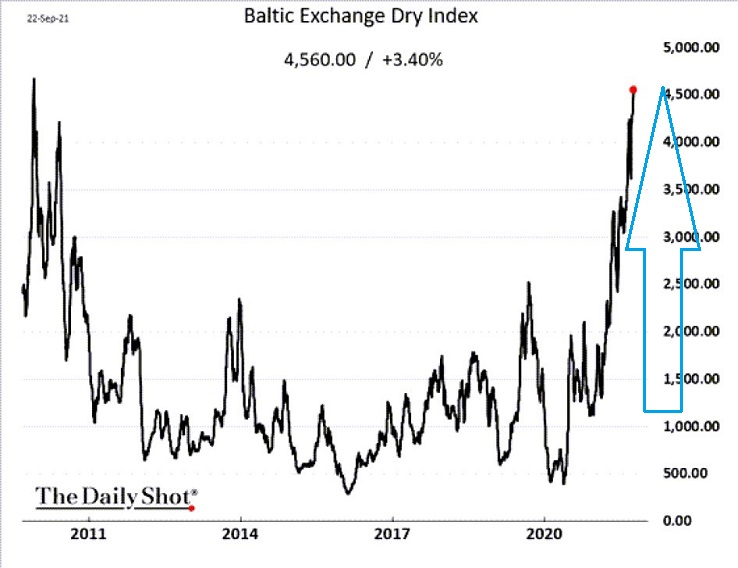

1. Inflation. Few investors pay attention to things like the Baltic Dry Index. That’s a mistake.

The index offers a way to track costs associated with the movement of raw materials. Specifically, one can examine the price required to move those materials by sea.

It’s one thing to note that the Baltic Dry Index has been skyrocketing. It’s another to recognize that a continuation of the inflationary trend could spell trouble for corporations and consumers alike.

If the Federal Reserve must battle inflation, committee members would likely terminate Fed money printing sooner and/or raise overnight lending rates faster. Are stocks genuinely prepared for rapid-fire tightening?

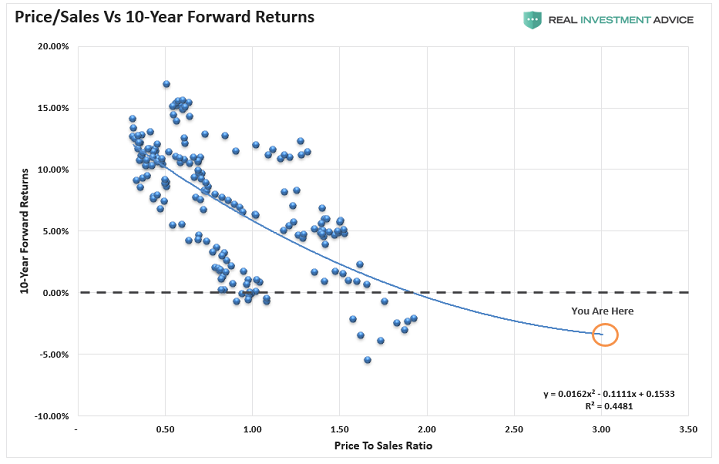

2. Valuation. The stock market has never been more overvalued on tried-and-true metrics. Market capitalization to GDP, PE 10, price to sales, price to earnings, price to book, the Q ratio, enterprise value to cash flow — you name it. Many of the valuation measures currently forecast negative returns over the next 10 years.

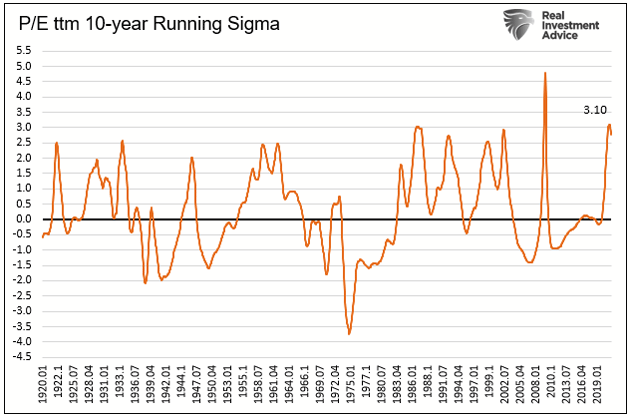

Financial analyst and money manager, Michael Lebowitz, recently calculated the number of standard deviations that the current month’s price-to-earning ratio is above or below a 10-year average. Two standard deviations above or below is uncommon; three standard deviations (a.k.a. “three sigma”) is considered rare.

The present-day reading of 3.10 “…matches or exceeds seven other peaks in the last 100 years.” And in all instances, the ratio eventually reverted to zero or lower.

According to Lebowitz, a reversion to zero standard deviations is synonymous with a 36% bear market decline. And that does not even account for the possibility of negative readings.

3. Price Movement. On the surface, the stock market looks unbreakable. The S&P 500 as well as other large cap barometers (e.g., Dow, Nasdaq, etc.) remain well above long-term moving averages. Beneath the surface, however, fewer and fewer stocks are gaining ground.

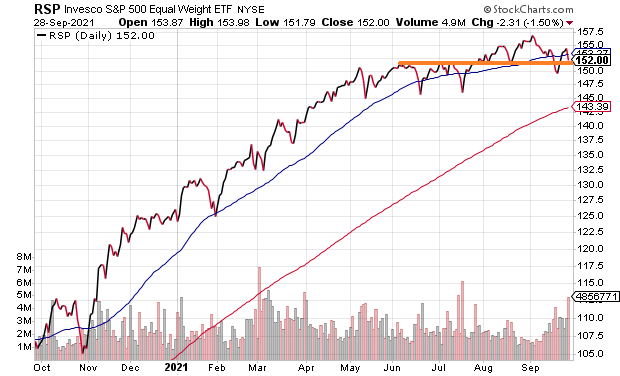

Consider the Invesco S&P 500 Equal Weight ETF (RSP). Whereas Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Google, and Microsoft have been able to carry the market-cap weighted S&P 500 index significantly higher over the last four months, equal weighting the 500 components shows a market that may be slowing.

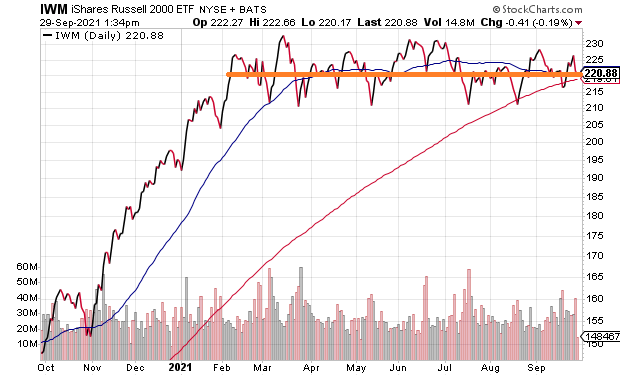

Did I say four months? Smaller companies in the Russell 2000 ETF (IWM) have gone nowhere for eight months.

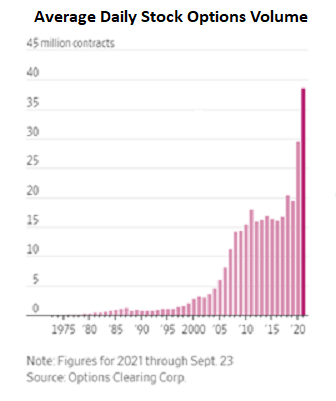

4. Options Mania. According to year-to-date data compiled by the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE), single-stock options with a notional value of $6.9 trillion changed hands through September 22. That is far and away beyond the $5.8 trillion in stocks that traded over the same time period.

In fact, 2021 is likely to become the first year ever with the value of options changing hands exceeding the value of stocks changing hands. And there’s only one reason for it. An unchecked belief that stocks can only go higher.

Shorter-term derivatives trading enhances returns on the way up. But on the way down? A downturn for stocks could turn catastrophic should margin calls force investors to sell.

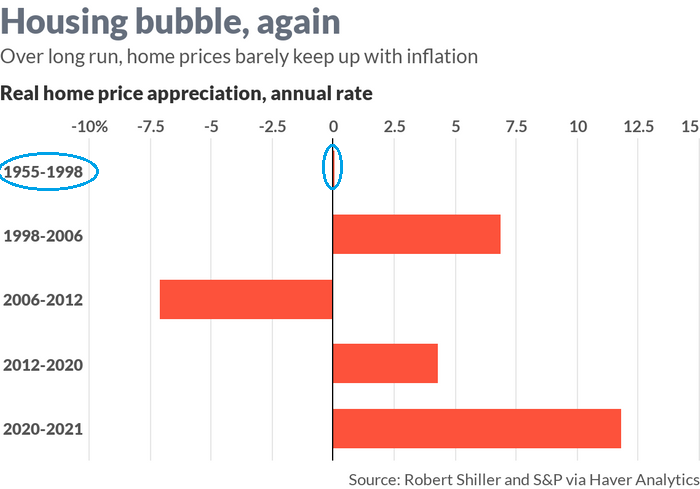

5. Housing Misfortune. Most folks think that residential real estate has a long history of success as an investment. They are wrong.

According to Case-Shiller, from 1901-2000, the average annual increase for homes was a mere 0.2% above the inflation rate. That’s not a lot to crow about.

Things changed when the 2000 stock bubble imploded. The Federal Reserve began to radically manipulate rates lower to stimulate the economy. Meanwhile, the federal government made it extremely easy for less qualified applicants to acquire property. Home prices rocketed accordingly.

Eventually, however, the Fed began to tighten the reins with higher overnight lending rates. Similarly, a number of lenders became more concerned about lending to people without a clear path to servicing the debts. As housing began to roll over in 2006, and as subprime debt woes went viral in 2007, the stock market collapsed in 2008.

Now we’re at it again. And while a housing bust is not likely to look exactly the same as it did in the 2006-2012 time frame, a period of depreciation is practically preordained. The only question is when.

With the Fed set to taper its bond buying activity, even small increases in mortgage rates could price out potential buyers. That might not be enough to send home prices into a tailspin. On the other hand, even a housing slowdown could drag on the economy and prove detrimental to stocks.

Would you like to receive our weekly newsletter on the stock bubble? Click here.